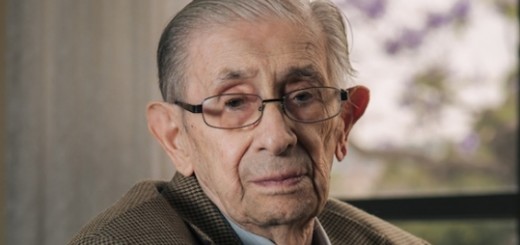

SURVIVOR: GEORGE BERCI

In October 1942, George Berci, then George Bleier, was ordered to report for forced labor. Along with 1,600 young men, the 21-year-old was transported from Budapest to a camp near Bereck, Hungary, near the Romanian border. During the day, in his assigned group of 400 men, George was marched into the mountains, more than an hour’s walk, where he dug anti-tank trenches from sunup to sundown, especially arduous in winter when the ground was frozen. At night he slept with his group in a large, cold cement bunker, using small branches he had collected in the forest as a mattress.

On one occasion, for some arbitrary transgression, Hungarian guards tied his hands behind his back and hoisted him up with a rope that had been thrown over a heavy branch. His feet lifted off the ground, and his arms bore all his body weight. George believes he became semi-conscious. “I couldn’t lift my arms for days,” he said. “It was terrible.”

On one occasion, for some arbitrary transgression, Hungarian guards tied his hands behind his back and hoisted him up with a rope that had been thrown over a heavy branch. His feet lifted off the ground, and his arms bore all his body weight. George believes he became semi-conscious. “I couldn’t lift my arms for days,” he said. “It was terrible.”

George Berci was born on March 14, 1921, in Szeged, Hungary, the only child of Alexander and Ella Bleier. The following year, his father was hired as the assistant conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, and the family, including George, his parents, maternal grandparents, uncle and great-aunt, moved into a two-room apartment in Vienna.

George’s father left for India in 1924, while the family remained in Vienna. George was made to begin violin lessons at age 4, and by the time he was 10 he was playing concertos.

In 1935, the political climate in Vienna shifted to the right. With no explanation, George’s non-Jewish friends stopped associating with him. And in his public school classrooms, he and other Jewish students were relegated to the back row.

That same year, his maternal uncle, who supported the family, lost his job with Electrolux in Austria, but was offered a position in Stockholm. George’s grandmother, however, vetoed the idea, and in 1936 the family moved to Budapest. George’s parents were divorced by this time.

At 16, forbidden to attend public high school, George was accepted into a private Jewish school. He financed his education by washing cars on weekend evenings, even in winter, and graduated in 1939.

Unable to attend university, George apprenticed for one year in an electrical shop and then worked for two years as a mechanical engineer.

George’s uncle was called into the military around 1940 and later killed in Russia. His father disappeared in 1941.

After spending more than two years at the labor camp near Bereck, wearing the same clothes throughout, George and the other prisoners were taken by train in January 1944 to a large railway center near the Polish-Czechoslovakian border. There, they unloaded ammunition from German trains and transferred it onto trucks.

According to George, they handled some highly explosive ammunition, casually tossing it to one another, assembly-line style. “What I remember is that the guards became very nervous. But I was coming to this phase in my life where I don’t care about life,” he said.

In June 1944, George and the remaining prisoners were put on a train headed to a concentration camp. The train, however, stopped to change engines in Budapest, where American forces were dropping bombs. The Hungarian guards, fearing the train would be hit, suddenly disappeared. “We disappeared, too,” George said.

Through Catholic cousins living in Budapest, George tracked down his mother, who was living in a “yellow star” apartment. George moved in.

Soon after, while looking for work, George was approached by a man who recognized his Viennese accent and led him to a hideout for the Hungarian underground. They produced false papers — such as birth certificates and employment papers — for Jews hidden throughout the city, and George was tasked with delivering these documents. “It was dangerous work,” he said.

During this time, Budapest’s Jews were forced into a ghetto. With his Red Cross papers, George was able to enter the ghetto, find his mother and bring her to his apartment.

Late in December 1944, with the Russian army surrounding Budapest, the Germans couldn’t transport Jews to concentration camps. Instead, they marched them to the Danube River, lined them up on its shore, and machine-gunned them, letting the bodies fall into the water.

In early January, fearing he and his mother would starve, George announced, “We are going to Szeged.” They went to a station for Russian military trains, the only available means of transportation, and, George, wearing a Red Cross armband and carrying a doctor’s bag, offered a soldier there two packages of sulfa drugs in exchange for a ride. Because gonorrhea was rife among the Russian military, his bribe was accepted.

On the train, George told his mother he wanted to be a symphony conductor. “You’ll be a doctor,” his mother answered. And on Jan. 5, 1945, with the Russians controlling the city, George enrolled in the University of Szeged’s medical school, changing his name to Berci to deflect anti-Semitism. To finance his education he cleaned instruments in the physiology department.

In Szeged, George’s mother met and married Frank Breszlauer.

George graduated from medical school summa cum laude in 1950. He then worked as a resident at the University of Szeged’s surgical clinic.

In 1954, George became an assistant in surgery at Postgraduate School of Medicine in Budapest, where he was very interested in experimental surgery and instrumentation.

Then, in October 1956, the Hungarian Revolution broke out. Two weeks later, a large Soviet force entered the city, opening fire on demonstrators in Parliament Square and severely injuring 250 of them. Casualties were taken to a hospital, where George and other surgeons operated day and night.

After that, George decided to leave Hungary. On Nov. 26, 1956, George, his mother and stepfather boarded a train, disembarking one stop before the Austrian border. They came to a cornfield where, in a group of 30 people, they set out on a three-mile walk in rain and snow to the border, which was guarded by Russian soldiers.

After they’d walked for a mile, falling to the ground whenever searchlights scanned the area, George’s mother gave up, insisting on returning to Budapest. But George dropped everything he had, including a small briefcase with some money, and, although he was barefoot because his shoes had become stuck in the mud, he carried her the rest of the way, an all-night journey.

They made their way to Vienna. There, George was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship and promised a job in Boston. But, as he believed the United States and Russia were on a collision course, he opted to go “as far away as possible from the next war” and chose Australia.

George settled in Melbourne, working as a technician and studying English, memorizing 100 words a day. Then, from 1957 to 1962, he joined the surgery department of two Melbourne hospitals, continuing his work in experimental surgery and optical technology.

In 1968, George came to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center as a visiting professor and never left. Today he is recognized as the pioneer who developed the techniques that serve as the foundation of all endoscopic and laparoscopic surgeries.

At 92, he is senior director of Minimally Invasive Endoscopic Research at Cedars-Sinai. In addition to teaching and researching, he enjoys classical music. He has been married to Barbara (Weiss) Berci since 1988 and is the father of three children from previous marriages — Kitty, born in 1950; Winton, 1955; and Nina, 1969. He has six grandchildren.

George said he doesn’t “beat his chest” that he’s a survivor. And he doesn’t talk about the Holocaust much, except to his children and grandchildren. “I’m very keen that the next generation should know about it,” he said.

Eyi je akoonu ti o niyelori!